2016 The Difference Research Grant

INTRODUCTION

Celebrities have been endorsing a wide range of products since the late nineteenth century (Kaikati, 1987). By some estimates, about 17% of advertisements that aired in the United States featured celebrities that endorsed products and brand in 2008 (Creswell, 2008), whereas advertisements using celebrities are about 40% of total advertisements in Korea (Do & Hwang, 2008). Because of popularity and effectiveness of celebrity endorsement, it has enjoyed much resonance among academics and practitioners (Vaughn, 1980). Current research aims to investigate how the effects of celebrity endorsed advertisement can vary depending on construal level

messages in the context of charity giving.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

Charitable Giving

The American participation rate to charitable giving is progressively increasing year by year (Giving USA, 2015). The 2010 Study of High

Net Worth Philanthropy (2010) estimated that total charitable giving would reach $55.4 trillion in 2052. The study also reports that the

largest source of charitable giving in 2010 came from individuals at 72% of total donations, followed by foundations at 15%, bequests

at 8%, and corporations at 5%. A variety of motivations drive philanthropic actions. Philanthropy research appears in very different disciplines including marketing, economics, social psychology, biological psychology, neurology and brain sciences, sociology, political science, anthropology, biology, and evolutionary psychology (Bekkers & Wiepking, 2010). Much research in the field of social psychology has dealt with helping behaviors in general, but these are a very broad category of actions that range from giving support to a stranger in an emergency situation, to donating an organ. In this study, in line with Bekkers and Wiepking (2010), charitable giving is defined as the donation of money to an organization that benefits others beyond one’s own family.

Celebrity Endorsement

Because celebrity endorsement makes ad message more memorable, credible and desirable (Miciak and Shanklin 1994), celebrity endorsed advertisements are considered one of the more effective ways of increasing people’s attention to an advertisements and enhancing persuasion (Choi & Rifon, 2012).

In line with this, McCracken (1989) demonstrated that celebrities’ images or characteristics are attached to the products, and those of

generated product meanings are transferred to consumers through consumption. It is called the matchup effect between a celebrity and the product being endorsed. Previous research have suggested that celebrity endorsement is more efficient and effective when perceived celebrities’ images or characteristics are matched well with products they are endorsed (e.g., Kahle and Homer, 1985; Kamins, 1990; Kamins and Gupta, 1994; Till and Busier, 2000).

In the context of charity giving, ad message plays an important role in drawing consumer attention, creating favorable attitudes, and

enhancing intentions to give. Because ad message encourages certain interpretations (Entman, 1993; Levin, Schneider and Gaeth,

1998), particular aspects can be highlighted and framed in order to make messages striking and have an influence on behaviors (Entman, 1993). Despite the importance of ad message in the persuasion, little research was conducted to investigate the relationship between ad message and celebrity endorsement in the context of charity giving.

Since the effect of celebrity endorsement in charity giving can vary depending on message types paired with, understanding their

relationship is essential to develop effective advertising strategies.

Construal Level Theory (CLT)

One of the most effective ways for message framing is that emphasizing how information is represented: abstract or concrete (Lee, Keller, and Sternthal, 2010; Trope, Liberman and Wakslak, 2007). Construal level theory applied psychological distance, which consists of four dimensions of perceived distance; temporal, spatial, social distance and probability (Trope and Liberman, 2011). As psychological distance increases from the object, individuals tend to use higher-level construal to represent the object, whereas as psychological distance decreases, individuals conceptualize the object in lower-level construal (Liviatan, Trope and Liberman, 2008).

In this theory, construal level is defined as the degree of abstraction at which goaldirected actions are represented in the cognitive hierarchy (Liberman and Trope, 1998; Vallacher and Wegner 1985, 1987).

Therefore, advertising messages construed at a high level are more abstract and emphasize the desirability of behavior in relation to

why certain behavior is necessary (Lee, Keller and Sternthal, 2010; Trope, Liberman and Wakslak, 2007). On the contrary, advertising messages construed at a low level are more concrete and focus on the feasibility of the behavior and thus pertain how to behave (Trope, Liberman and Wakslak, 2007).

Current research proposed that the effect of celebrity endorsement in charity giving would be moderated by construal level messages.

Most of research findings suggest that celebrities have a significant influence on consumer behaviors through their transferrable images such as expertise, trustworthiness, attractiveness, familiarity, and likeability that are also considered as factors for favorable effects

to the individuals’ message acceptance (Ohanian, 1990; 1991).

Especially, previous research demonstrated that familiarity and likeability for an endorser lead to different levels of effectiveness of an advertising message (McGuire, 1985; Amos et al., 2008).

Considering the familiarity and likeability are determinant factors for social distance, which is one dimension of psychological distances, we can expect that people would perceive a celebrity psychologically near than non-celebrity. From the perspective of cognitive processing, this suggests that celebrity endorsement would be more effective when paired with concrete messages than abstract messages. It is because a celebrity and messages would be construed at the same levels and this congruent processing leads to favorable evaluations (Trope and Lieberman, 2010). In contrast, people would perceive an ordinary endorser as psychologically distant in the context of advertisement. In sum, we can initially hypothesized that H1: Individual will show more positive evaluations for celebrity endorsed advertisement when it is presented with concrete messages than abstract messages. H2: Individuals’ evaluations for non-celebrity endorsement will not be affected by types of construal level messages.

METHOD

An experiment was conducted to investigate our proposed hypothesis. A2 (types of endorser: celebrity vs. non-celebrity) ×2 (construal level: abstract vs. concrete) between-subjects design was employed. Both independent variables were manipulated in the study. Four black and white advertisements for the hunger campaign were created. On the basis of the results of pretest, Brad Pitt and an anonymous middle-aged man were selected as a celebrity and non-celebrity endorser for hunger campaign. Construal level was manipulated as either abstract or concrete message framing. For example, the headline of the advertisement was manipulated as “Protect the world. You can make the world full” in the high construal level condition, whereas the message was manipulated as“ Your

$0.25 can provide a child with enough food to grow up healthy.” in the low construal level condition.

Sample, Procedure, and Measures

A total of 167 female college students (Age M = 23.1) participated the experiment with extra credit. They were randomly assigned to one of the four conditions. Before the exposure to the advertisement, participants measured the charity support importance which refers to (3 items, a seven-point Likert scale; 1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree; M = 5.62, SD = 1.12; α =.872). Participants were then shown an advertisement for one minute. After viewing their assigned advertisement, participants proceeded to answer questions concerning the main dependent variables of the study:

Attitude toward advertisement (Aad; 9 items, a seven semantic differential scale; e.g., bad - good; M = 4.46, SD = 1.11; α = .875)and Advertisement believability (8 items, a seven semantic differential scale; e.g., untrustworthy - trustworthy; M = 4.51, SD = 1.26; α =

.935). Participants also answered how likely the spokesperson in advertisement looks like a celebrity (1 item, a seven-point Likert scale; 1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree; M = 5.10, SD = 1.94) and whether construal level messages is abstract or concrete (1 item, a seven semantic differential scale; M = 4.21, SD = 1.8). Finally, participants answered to the demographic questions such as age, gender, ethnicity, and debriefed.

RESULTS

Manipulation Check

To assess whether the endorsers and construal levels framed in the four advertisements were indeed perceived to be as we intended, t-tests were conducted. The results suggested that participants in the celebrity condition (M = 6.64, SD = .92) more likely to think their endorser as a celebrity than non-celebrity condition (M = 3.45, SD = 1.28, t = 22.236, p < .001). Also, participants in the high construal level message evaluated the message to be less concrete (M = 3.42, SD = 1.67) than low construal level message condition (M = 5.04, SD = 1.58, t = -3.431, p <.01). Thus, the types of endorser and construal level manipulations were effective and successful.

Hypothesis Testing

The hypothesis was tested via a two-way ANCOVA on the three dependent variables. The potential confound effect of charity support importance was controlled as a covariate. Results of the ANCOVA revealed that the main effects for types of endorser and construal level were not significant for all dependent variables (ps >.05). However, as predicted, the types of endorser X construal level interaction was significant for all dependent variable (FAad = 5.376, p< .05; Fbelievability = 3.504, p < .01). To examine the interaction effects, planned contrasts were conducted. The results showed that participants showed more favorable attitude toward advertisement when a celebrity endorser is presented with the concrete message (M = 4.60, SD = 1.06) rather than abstract message (M = 4.15, SD = 1.04; F = 5.862, p < .05). Participants also perceived the celebrity endorsement as more believable when presented with concrete message (M = 4.60, SD = 1.19) rather than abstract message (M = 4.12, SD = 1.24; F = 5.422, p < .05). Thus, H1 was supported. In contrast, when non-celebrity endorsement was presented, participants’ attitude toward advertisement and advertisement believability were not differed depending on the construal level messages paired (ps >.1).

Thus, H2 was also supported.

DISCUSSION

Current research examined the effects of celebrity endorsement on charity giving with the moderating role of construal level messages.

As expected, participants showed more favorable responses when the celebrity endorsed advertisement is matched with concrete messages than abstract messages. On the other hand, participants’ response to the non-celebrity endorsed advertisement was not different depending on construal level messages. Moreover, the results showed that there was significant covariate effect of individuals’ the charity support importance, indicating that individuals’ concern and thought for issue has an impact on the relationship between two independent variables. The results suggest that psychological distance could be an underlying mechanism for the interaction effect between types of endorser and construal level. It seems that the higher level of exposure and interests in celebrities make people being familiar with celebrities. As Erdogan(1999) defined, familiarity refers to the knowledge of source through exposure. Thus, a lot of knowledge would lead individuals to feel objects close to them, which subsequently conceptualize it in concrete level, whereas scant knowledge would lead individuals to feel objects far away from them, which subsequently conceptualize it in abstract level. Accordingly, it is reasonable to think that if a middle-aged man was less perceived as a celebrity (less than M= 3.45; a seven Likert scale), people would show more positive evaluations when the noncelebrity endorsed advertisement is presented with abstract messages than concrete message. The pattern of results for the non-celebrity endorsed advertisement support this assumption (Attad for non-celebrity endorsement: Mabstract = 4.66, Mconcrete = 4.48; Believability for non-celebrity endorsement: Mabstract = 4.86, M concrete = 4.54). Current research also has limitations and future implication.

All participants were female and there would be gender differences.

Also, even though the psychological distance was proposed as an underlying mechanism for interaction effects, current research did

not empirically demonstrate it. Moreover, current research measured the attitude toward advertisement and advertisement believability as dependent variables. Beyond the attitude toward advertisement, some variables closely related to actual behavior such as willingness to donate should be included in future research. Lastly, considering that the context of charity giving easily amplifies social desirability bias inherently tied to self-report method (Carrigan and Attalla, 2001), the qualitative approach is needed to develop compelling theory to explain this phenomena (Carrington et al., 2014). However, to the best of our knowledge, this research is the first to extend these two domains together into the context of charity giving. Current research also provides practitioners practical implications to develop advertising strategies for encouraging people to participate in charity giving.

Backgroundand Research Hypotheses

The growing popularity and use of social networking sites (SNSs) has prompted a great deal of research on advertising acceptance as a crucial factor for advertisers and marketers seeking to build and cultivate relationships with their consumers at minimalcost(Campbelland Marks 2015). Considering the fact that the acceptance of brand messages by SNS users leads to active promotion of the message, it is im portant to maintain positive consumer perceptions toward advertising on SNSs.

The advertising industry has begun using a new format of online advertising, called“ native advertising”, in the hopes of striking a balance between penetrating advertising and non-intrusive advertising. Native advertising distinguishes itself by taking advantage of its non-intrusive nature by placing relevant advertising information within the feed with minimal disruption. Native advertising, as a form of brand or product-related communications created by a brand of a publisher, appears within a SNS feed, designed to imitate the unique style and format of the particular SNS content to create seamless integration.

Despite the increased attention given to native advertising, there is dearth of knowledge regarding this unique form of advertising, especially in the context of SNSs. Drawing upon the consumer socialization framework (Moschis and Moore 1979; Ward 1974), this study attempts to explore the role of consumer socialization in consumers’ acceptance of native advertising on SNSs, virtual space for consumer socialization that can facilitate various consumptionrelated communications (Lueg et al. 2006). Consumers actively share information about products and brands on SNSs, which promotes the consumers’ socialization process on SNSs (Wang, Yu, and Wei 2012).

This study seeks to examine the impact of socialization antecedentspeer communication, social media dependency, and attitude toward social media advertising in general-on consumers’ acceptance ofnative advertising on SNSs. In line with the consumer socialization framework, the following hypotheses are put forth:

H1: Peer communication about consumption will be positively related to consumer acceptance of native advertising on SNSs.

H2: Positive peer communication about consumption on SNSs will be positively related to consumer acceptance of native advertising on SNSs.

H3: Negative peer communication about consumption on SNSs will be negatively related to consumer acceptance of native advertising on SNSs.

H4: The level of social media dependency will be positively related to consumer acceptance of native advertising on SNSs.

H5: Attitude toward social media advertising in general will be positively related to consumer acceptance of native advertising on SNSs.

The judgment of ad appropriateness has to do with“ whether the marketer’s tactics seem to be moral and normatively acceptable” (Friestad and Wright 1994, p. 10) and whether marketers are attempting“ to persuade by inappropriate, unfair, or manipulative means” (Campbell 1995, p. 227). The judgment of ad appropriateness is one of the measures to assess a consumer’s persuasion knowledge that is activated in response to a specific persuasive attempt, such as advertising (Ham, Nelson, and Das 2015). When consumers perceive covert marketing tactics to be appropriate, they are less likely to be affected by persuasion knowledge in evaluation of the advertising and the brand (Wei, Fischer, and Main 2008; Yoo 2009). Likewise, consumers’ evaluation of native advertising on SNSs might be influenced by their perceived appropriateness of the ad. The study advances the current knowledge by examining the moderating role of consumers’ perceived appropriateness of ad (Campbell 1995)—that is, consumers’ perception of appropriateness of native advertising on SNSs. If native advertising on SNSs is perceived as manipulative and inappropriately persuasive, consumers might evaluate the ad negatively, regardless of the impact of socialization agents. Thus, this study anticipates that consumers’ perceptions of ad appropriateness moderate the effects of socialization agents on acceptance of native advertising (H6).

Method

An online survey was conducted on a sample of Facebook users (N = 399, age M = 35, Female = 50%) recruited from Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk). The questionnaire was designed to measure participants’ engagement in peer communication and both positive and negative communication related to products/brands with their peers on SNSs, social media dependency, attitude toward social media advertising in general, and perceived appropriateness of native advertising. Acceptance of native advertising was assessed by measuring the respondents’ attitude toward native advertising, intention to recommendation native advertising, and intention to recommend brands appeared in native advertising.

Results

A series of hierarchical multiple regressions was conducted to test the hypotheses regarding the effects of the consumer socialization agents on acceptance of native advertising on SNSs. In examining the role of each socialization agents, the results showed that there was no significant impact of peer communication on perceived native ad attitude, native recommendation intention, and brand recommendation intention. Thus, H1 was not supported. Positive product/brand communication among peers on SNSs found to be a significant predictor for perceived native ad attitude (β=.20, p<.001), native recommendation intention (β=.29, p<.001), and brand recommendation intention (β=.32, p<.001), which confirmed H2. Negative product/brand communication among peers on SNSs demonstrated partial support for H3, which found to be as a significant predictor only for perceived native ad attitude (β= -.12, p<.01), but not for native recommendation intention and recommendation intention. The effect of social media dependency was found to be significant and it was the second strongest predictor for perceived native ad attitude (β =.12, p<.001), native recommendation intention (β=.16, p<.001), and brand recommendation intention (β=.17, p<.001). Thus, H4 was supported. The result showed that attitude toward social media advertising in general was found to be the strongest predictor for perceived native ad attitude (β=.63, p<.001), native recommendation intention (β=.43, p<.001) and brand recommendation intention (β=.39, p<.001) which supports H5. The results indicated that there was partial support for H6 that the effects of consumer socialization agents would be moderated by perceived appropriateness of native advertising.

Conclusions

This study highlighted the mechanism by which consumers accept native advertising on SNSs by examining the antecedents of consumers’ acceptance of native advertising by applying and extending the consumer socialization framework. Through examination of the influences of both positive and negative peer communication on SNSs, the study revealed that only positive communication about consumption on SNSs was found to be a significant predictor of acceptance of native advertising on SNSs.

However, negative peer communication about consumption was found to be influential on consumers’ attitude toward native ad on SNSs. This discrepancy between the role of positive and negative peer communication might have resulted from the different natures of consumer motivations for engaging in positive versus negative communication related to consumption on SNSs. SNSs users are motivated to participate in positive electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) and engage in recommendation behaviors as a mean for expressing themselves, socializing, and seeking information and entertainment on SNSs (Kim 2014). However, they might be relatively reluctant to share negative opinions in a public space because active sharing of negative opinions often requires high involvement and loyalty (Verhagen, Nauta, and Feldberg 2013).

The findings revealed that social media dependency had a positive influence on the acceptance of native advertising, suggesting that consumers’ acceptance of native advertising on social media heavily depends on their usage and level of media experience. These findings support the relationship between social media dependency and consumer engagement on SNSs (Tsai and Men 2013). Among the five antecedents, attitude toward social media advertising in general was the strongest predictor of acceptance of native advertising on SNSs. It is important for advertisers and social media marketing practitioners to pay attention to consumers’ general attitude toward advertising on SNSs because consumers’ predetermined attitude toward social media advertising might carry over into their acceptance of native advertising. For brands to facilitate consumer acceptance of advertising in a native format and build meaningful consumer relationships on SNSs, native advertising campaigns should be preceded or accompanied by the success of a series of social media advertising practices.

The findings of this study shed light on the role of consumers’ perceived appropriateness of native advertising on SNSs. It is worth paying attention to the value of consumers’ perceptions as to whether they regard native advertising as appropriately executed and targeted on SNSs. It is imperative that advertisers consider the appropriateness of native advertising as the key determinant of its success in the social media environment.

Extended Abstract

Until recently, emotions have been considered interruptions or distractions in decision- making processes, rather than a vital informational source to solve our daily problems (Raghunathan and Trope 2002). Recent advances in psychology and neurology, however, have suggested that emotional and cognitive systems in a human brain are far more intertwined than originally assumed and emotions are important resources to reach reasonable decisions, fueling the movement that emphasizes the importance of emotions in thinking processes (Damasio 1994). Following this new perspective, the present study suggests the concept of consumer emotional intelligence (CEI) as a useful explanatory construct that is capable of accounting for individual differences in the persuasiveness of advertising. This is particularly meaningful because emotional ability has received scant attention in advertising literature, while a substantial amount of research has examined the role that cognitive ability plays in the persuasiveness of advertising. This study aims to address this insufficiency by examining the specific role that emotional ability plays in persuasion.

CEI anditse ffectsonad vertising persuasi veness

With the recent development of a comprehensive conceptualization and measurement of emotional intelligence (EI) in social psychology, Kidwell et al. (2008a) developed the concept of CEI, which is specifically applicable in a consumption context. CEI implies that consumers possess“ the ability to skillfully use emotional information to achieve desired consumer outcomes.” (Kidwell et al. 2008a, p.154). Kidwell et al. developed measurement scales to assess CEI(so called“ CEIS”) and they successfully supported the reliability as well as the discriminant and nomological validity of it (Kidwell et al. 2008a). Grounded upon this construct, studies further showed thatemotionally intelligent consumers were likely to make high-quality food choices as well as good brand choices (Kidwell et al., 2008b), and reach constructive solutions to resolve conflicts in consumerbrand relationships (Ahn, Drumwright, and Sung 2016).

The theoretical and empirical foundations of CEI offers a valuable approach to understanding individual differences in responding to affective information in advertising. It is expected that consumers who are high in CEI would be able to prioritize their emotions and think and act judiciously based on how they feel; therefore, they should be able to control their desires and impulses to buy the brands they see in advertising. CEI is associated with a greater reliance on deliberative regulation of emotions, so that people with high CEI analyze and evaluate their emotions with a vigilance that allows them to arrive at accurate judgments and avoiding premature consequences. In other words, when individuals are emotionally intelligent, they are likely to maximize the accuracy of their decision outcomes by carefully controlling emotions that are elicited by advertising messages. The higher levels of calibration on emotions (i.e., high level of CEI) will weaken the persuasive emotions evoked by ad messages. This study thus hypothesizes that people with high CEI will show less favorable attitudes toward the emotion-evoking ad, attitudes toward the brand advertised, and purchase intentions than people with low CEI.

CEI andregulator y focustheor y inad vertising

This study further uses regulatory focus theory to investigate the moderating effect of CEI on advertising messages. It argues that the

effect of CEI on persuasiveness of messages will be stronger when messages in ads are promotion-focused rather than when they are

prevention-focused, because a promotion-focused ad encourages more emotional responses from consumers. This is in part because

those with a promotion focus prefer to make decisions using feelings, while those with a prevention focus prefer to make decisions with reasoning. Pham and Avnet (2004) demonstrated that participants primed with a promotion focus had more affective responses to the print ad than those with a prevention focus, because the accessibility of an ideal end state (i.e., outcomes of promotion focus) triggers the reliance on subjective affective responses to the ad. On the other hand, a vigilant and risk-adverse form of exploration evoked by a prevention focus triggers reliance on analytical reasoning rather than reliance on emotions; thus, people with a prevention focus were less likely to have emotional responses to the ad. Pham and Avnet (2008) further documented that emotional inputs in judgments were more heavily weighted under the conditions of a promotion focus than a prevention focus. Studies consistently indicate that persuasive claims with a promotion focus evokes more emotional responses than those with a prevention focus.

Method & Results

To test the hypotheses, a 2 (CEI: high vs. low) · 2 (ad message: promotion vs. prevention) between-subjects factorial design was employed. This study also controlled for variables that might bias the result, including the level of product involvement and concern about heart health because the ad stimuli used in the current study specifically highlighted one’s heart health. Professional advertising artists initially created several sets of ads with various verbal expressions. Through a pretest (N = 45), a final set of ads for the main study was chosen which had no significant difference in terms of attitudes toward the ad, but did show the difference of perceived regulatory focus across two conditions. A total of 162 undergraduate students in the U.S. participated in the study. The results of ANOVA indicated that the ad stimuli successfully manipulated as intended.

Consistent with the expectation, the results of ANCOVA showed that there was a significant main effect of CEI on attitudes toward the ad (F(1,156) = 4.52, p <.05), attitudes toward the brand advertised (F (1,156)= 7.99, p <.01), and purchase intention (F (1,156) = 4.61, p <.05). High-CEI consumers showed less positive attitudes toward the ad than low-CEI consumers (M = 4.32 vs. M = 4.71). The same pattern was observed for attitudes toward the brand (M = 4.02 vs. M = 4.53) and purchase intention (M = 3.48 vs. M = 4.00).

Additionally, there was a significant interaction effect between CEI and regulatory focus on attitude toward the ad (F (1,156) = 13.55, p < .001), attitude toward the brand (F (1, 156) = 5.35, p <.05), and purchase intention (F (1,156) = 5.34, p <.05). As expected, the effect of CEI was strong when the ad messages were promotion-focused while this effect was not strong when the ad messages were preventionfocused.

Implications

This research provides several new theoretical contributions to the field, as it is the first study (to the best of this author’s knowledge) to examine the role of emotional intelligence in an advertising context. The most important contribution is that this study empirically demonstrates that one’s level of CEI influences the persuasiveness of messages in ads, which suggests that CEI is an important individual difference to consider in predicting consumers’ responses to advertising. The study also provides a theoretical contribution to regulatory focus literature, as it demonstrates that different selfregulatory approaches (i.e., promotion vs. prevention focus) are related to the degree to which ad messages evoke emotional vs. analytic responses. Another contribution of the current study is that it employed the ability-based measures of EI rather than self-reported measures. Although most studies on individual differences have relied on self-reported measures to capture the predispositional traits of participants, this approach has been proven ineffective for measuring individual traits, because self-reported measures are susceptible to social desirability bias. Thus, the ability-based measure in this study may produce more accurate and pertinent knowledge about individual differences. In summary, the findings of this study demonstrated a scholarly need for greater attention to consumer emotional ability in order to

understand the persuasiveness of advertising.

Understanding ad effectiveness involves a highly complex configuration of cognitions and emotions. While a single study cannot completely articulate such complex phenomena, the findings of the current study may offer a useful theoretical foundation for building theory in the consumer emotional intelligence literature and provide an additional avenue for advertising research.

'Archive > Webzine 2016' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 2016/07-08 : Thank You Creativity (0) | 2016.08.08 |

|---|---|

| 2016/07-08 : 광고회사에 다니면 비로소 알게되는 것들 (0) | 2016.08.08 |

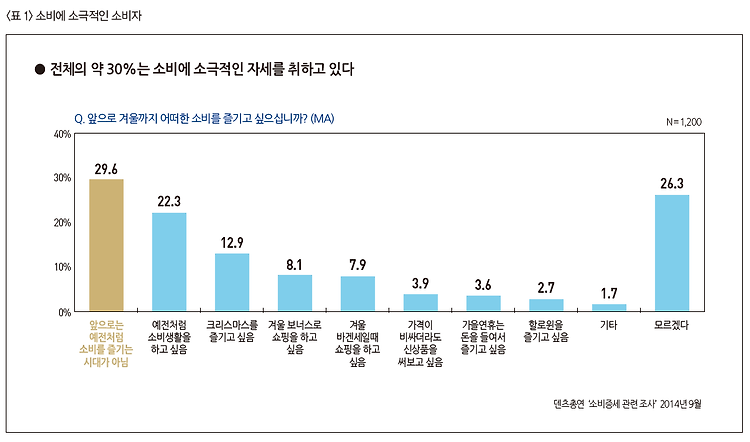

| 2016/07-08 : ‘생활시간 조정 ’ , 일본의 새로운 마케팅 트렌드를 만들다 (0) | 2016.08.08 |

| 2016/07-08 : 지금, ‘왕홍(网红)’이 王이다 (0) | 2016.08.08 |

| 2016/07-08 : 소비자에게 ‘경험’을 제공하라 (0) | 2016.08.08 |